The End of the Road

London, England.

The numbers are dizzying. But they only tell half the story.

Well,

As I prepare for my flight at Gatwick, and a comparably quick trip back to Australia, I thought I’d take a moment to look back over the whole thing - an overland trip around half of the planet.

This was going to be a post about the numbers I’ve crunched on this trip, which has undoubtedly been the biggest undertaking of my life.

While circumstances made it tricky to log everything in real time this year, I did manage to keep a detailed record of every commute - how I made it, and how long it took.

At the start, I was looking forward to seeing the absurd stats that would be thrown up by the end. But as I review them now here, they seem cold, and somewhat insignificant. The numbers provide some insight, but in the end, tell only a small part of this story.

In any case, here they are:

I’ll arrive home on September 12, having left on January 11. That’s 244 days in total - 8 months on the dot.

I travelled ~ 23,500 overland kilometers, across 36 countries using:

83 buses, 23 cars & shared taxis, 14 trains, 7 ferries, 3 hikes, 2 bike rides - and a solitary tuk tuk for the final 10 ks to the Thai/Laos border.

Xi'an, China: This was a typical commute in China. The slow train from Xi'an to Beijing.

Unfortunately, I was forced to take four short plane trips (Darwin to Dili - 30 minutes, Kupang to Maumere - 20 minutes, Jakarta to Singapore - 1 hour, Aktau to Baku - 25 minutes). But I’m comforted by the fact I barely flew over an inch of land - at the end, I was in the air less than 2.5 hours.

All up, I spent 754.5 hours on the move (an entire month). Around 3 hours a day - averaging just 31 kilometers per hour.

The Governor: The Governor of Arkhangai Province, Mongolia, Munkhnasan Tsogoo.

It sounds slow, but consider a worker who lives in the outer suburbs of a major city. For many of them, a 3 hour commute every day is quite common.

The longest unbroken journey I took was 40 hours - Kunming to Xi’an, in China, via the slow train. It was not the most uncomfortable though: that was an overcrowded train on a 40 degree day from Nukus, Uzbekistan to Beyneu, Kazakhstan.

I encountered 26 different languages, and 8 different alphabets.

I spent money in 28 different currencies.

For almost all of the trip, my budget of AUD$30/Day (US$22 / €18.50 / £16.50), was rarely broken.

When I hit the EU, though, that was blown out of the water.

The stats are interesting, sure. But this kind of story isn’t one best told by numbers.

All those quantifiable, obvious differences between countries and regions seem insignificant when compared with the deeper qualities they shared.

I struggled at times trying to identify the connective tissue of this journey. Occasionally it felt disjointed: like a series of small, unrelated trips, squished together.

But there was one consistency, something that did really bind this trip. And that was the endless unsolicited offers of help, assistance & hospitality.

It was the young family who drove me 10 hours into the East Timorese highlands; another family who drove me hundreds of kilometers across western Mongolia; the Pamiris who housed me in a remote village in Tajikistan; the border guard who looked after me in Afghanistan; the two lads who gave me a tour of their Uzbek city, Nukus, and bought me dinner, despite earning just $200 a month; the Armenian who invited my hitchhiking partner and I for a feast in his mountain home; the highlander who offered us generously her bounty of freshly picked wild-berries; and the refugee-turned-dry cleaner who treated me like a son in Bosnia. And there were, of course, others.

Of equal value though were the life-affirming, often banal mistakes that cost me time, money, and fun. They made me realise that no matter what the problem is, there’s always an answer - somewhere.

They ranged from silly but consequential errors, like not preparing my Azerbaijan visa early enough, a mistake that sparked a chain reaction of misfortune, left me stranded in Western Kazakhstan for two weeks, and cost me the chance to visit Iran.

Then there was the mundane, like the time I sat on an ice cream in Prague, and trudged the city with banana-coloured droplets running down my legs.

There were countless times I arrived in cities at ungodly hours, mapless, unprepared, and confused.

But not once did I sleep on the street: there was always someone willing to offer a hand, or a room.

The story of this journey is also told in things I can’t count.

Armin: My host and self-appointed tour guide in Prijedor, Bosnia.

Yerevan, Armenia: Angus soaking up the scene.

Tsetserleg, Mongolia.

Not once was I threatened, intimidated, beaten, bruised, scared or even seriously pestered. My only experience with theft was when a homeless Mongolian snatched a bottle of water from my hand, drinking it in desperation.

Looking back, it feels like the countries with the worst reputations tried their hardest to make me feel welcome. I received dire warnings about certain locations before I left. While not being naive to real dangers in the world, my belief that such dangers are the manifestation of a tiny, vulgar minority has been reaffirmed after these last 8 months.

I’m often asked what the ‘craziest thing that happened’ was. Well, there was no one particular moment of life-threatening danger, at least, not at the hands of others.

The closest call came in Georgia, when I waded into a fast flowing river and my feet came unstuck under the force of the current.

With Angus in Georgia: My brother came to visit along the way, joining me for a 76 kilometer trek in the Georgian Highlands. It was on this hike I was saved by the Germans.

My only saviour was the good will of a group of German hikers, who had waited for my brother and I to reach the river so they could help us cross. Without the German’s rope around my waist - and the three of them holding its other end - the dispassionate glacial melt might have carried me to my end.

The weirdest occurrence probably happened in Afghanistan. One morning, in a town where the Taliban are completely unwelcome, I shocked a local woman who was busy farming in her field. My beard was thick by then, and I was traipsing the backstreets taking photos. Upon seeing me, she screamed, and ran away in terror. I’m almost certain she thought I was Talib, some of whom have previously snuck in and raided the surrounding areas. In fear of being wrongly identified, I quickly returned to Tajikistan.

Letting go in Georgia: Often during the trip, my fate was in the hands of others. Here, I get a lift up one of the world's most dangerous roads, in Georgia.

But despite being fully exposed to the unpredictability of life on the road, I never ran into serious trouble.

It’s easy to think that maybe I’m just ‘lucky’. But the more travellers I meet doing similar trips, the more I realise my experience is the norm - not the exception. To run into misdeeds or misadventure is the result of exceptional bad luck - often nothing else.

There are also the experiences that root this trip firmly in this moment in history.

The President of Timor Leste: Francisco Guterres addresses his military.

Dili, East Timor. A soldier parading.

I snuck into the press-pool to watch the now-former East Timorese president address his military. I talked asylum policy with a Hazara teenager stuck indefinitely in Indonesia. I saw the brutal securitisation of Western China. I interviewed a women's-rights activist MP in Bishkek’s parliament after a horrific bride-kidnap-turned-murder in Kyrgyzstan. I travelled to northern Afghanistan on the day the Taliban and Kabul announced an historic ceasefire (that was soon broken). I saw overt evidence of increasing authoritarianism in Turkey. There was a constant presence of Syrian refugees in places such as Armenia, Turkey, and the Balkans. A Bulgarian farmer declared his admiration of Donald Trump to me. I drove through central Germany during a once-in-a-century drought. And I saw swarms of British travellers soaking up Europe just months before their small island is cast into a self-imposed political exile in the North Atlantic.

Aida Kasymalieva: A Kyrgyz MP, Aida is leading the fight against bride kidnapping in Kyrgyzstan - a scourge that still exists in an otherwise modernising society. I interviewed her in Bishkek - her optimism and resillience was an inspiration.

Mongolia's Future: Who knows where this young kid will end up. He was glued to my side during a train trip from Zamiin Uud to Ulaanbaatar.

Zugvand, Tajikistan: Nina, left, ran over and introduced me to her and her daughter, Julia, in slow Russian, as if she was practicing. "Izvinitye! Menya zovut Nina. I eto Julia".

Zugvand, Tajikistan: This was my bedroom for three nights. I was hosted here by Bek, a 65 year old Pamiri man who had spent 45 years as a taxi driver. His son, Alibek, had invited me to stay after giving me a ride.

I also saw Jared Leto on a side street in Krakow.

We live in a unique, troubling moment in the history of our shared planet. It has been a rare privilege to explore it from so many different angles, in one fell swoop.

As I sit here writing, in London, I can only really begin to digest what this trip has been. Time will help these memories ferment, and they may take on greater meaning and context.

While I'm in a reflective frame of mind, I’m also keenly anticipating what’s to come: a return to my hometown, Adelaide, where I’ll live for the next little while.

Kupang, West Timor, Indonesia: A local fishmonger in the town's main fishmarket.

Laos: In a small village wrecked by poverty, this smiling, happy child was much quieter than his friends.

After many months of patient solitude, often only broken by fleeting acquaintanceships, I’m excited to re-explore my own place, and hear the language of my own people and region.

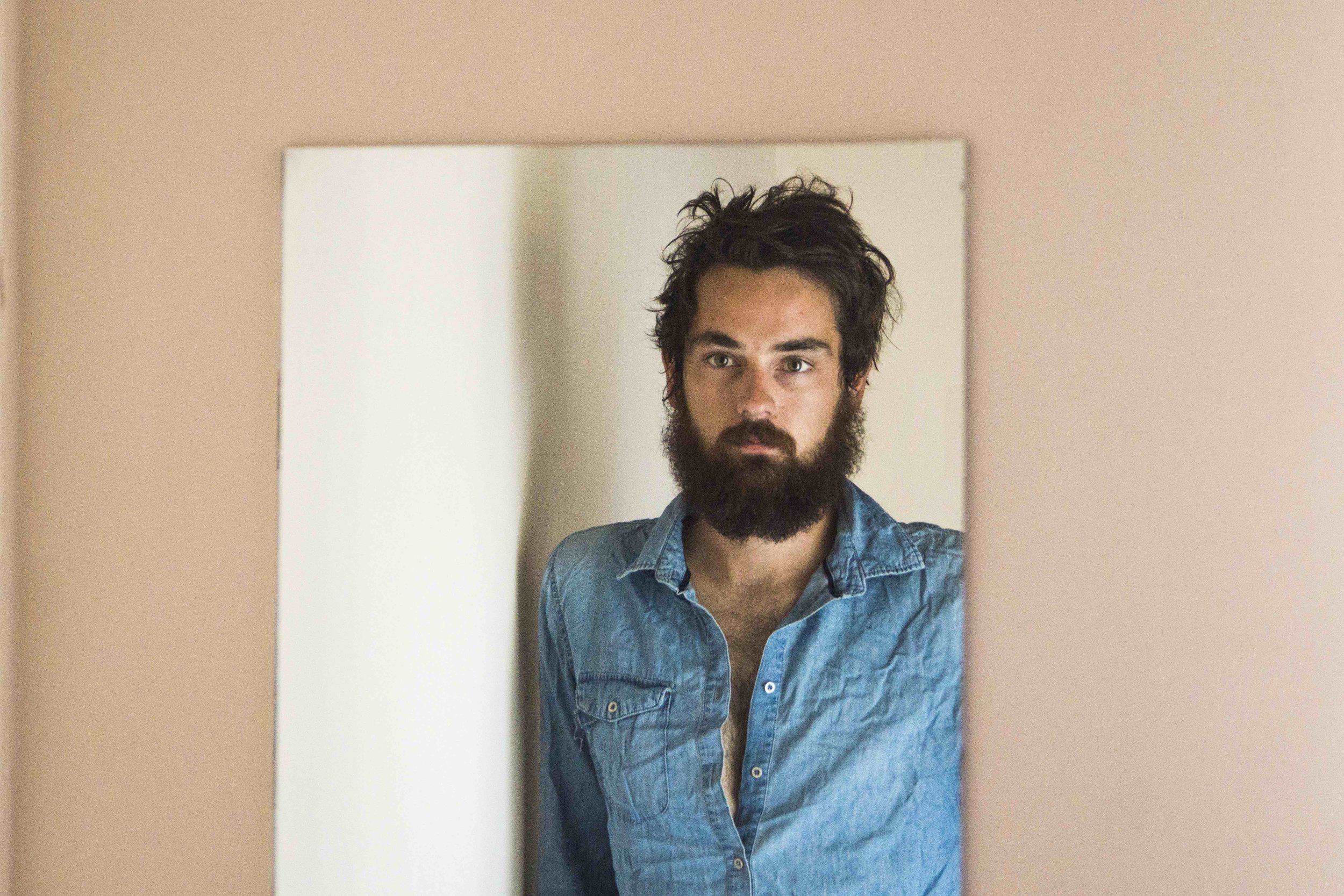

More than anything else, after half a year, I can’t wait to be reunited with the most important person in my life: Emily, my long-suffering girlfriend who never pushed back against my idea to drop everything for this very wild, very solo trip that spanned three continents.

Few are lucky to be in a relationship with someone so encouraging of their ideas, irrespective of the consequences those ideas might bring to the relationship. The risks I took in changing course to realise this childhood ambition - sacrificing a delightful, stimulating, fun life in bustling inner-Sydney for an uncertain future - were not my risks alone. Despite this, I can’t recall a conversation where Emily offered anything but support for a personal goal of mine that she knew wouldn’t die. Stoically, selflessly, she watched and supported me as I followed that goal.

That’s as good as it gets.

Day 1, Woomera, South Australia: Emily celebrating my birthday in the desert.

Emily.

I’ll post some more soon, and fill in the gaps of some logs I missed (particularly over these last few frantic weeks) as well as share some favourite photos, stories and more. But this will be my last post from the road itself.

To those who followed along, thanks for reading.

Maybe my missives have helped you come to the same simple conclusion I have: the world, after all, isn’t such a scary place.

Eddie.

Westminster Bridge: I found this a stirring site. The kids in the foreground are standing on barricades erected to prevent a terrorist attack like the one that killed 6 people here in 2017. Instead of cowering, the multicultural British community carry on, relishing in the sunshine, and utilising the barricades as a viewing platform.